I’m a romance ghostwriter. In my twelve-year career, I’ve written over a hundred romance titles for clients across practically every subgenre you can name—paranormal, dark mafia, reverse harem, contemporary, historical, you name it. If it has an HEA and someone’s pulse spiking by chapter three, I’ve probably written it.

But of all the books I’ve written, the one that bears my actual name is Ostakis, an MM science fiction romance. And the series I’m developing independently—The Justix Files—is also MM. People who know my work sometimes ask why. Isn’t the market bigger for straight romance? Aren’t I limiting myself?

No. And here’s why.

The Story That Wouldn’t Work

The Justix Files started life as a male/female romance. A brilliant LAPD detective—sharp, unconventional, burdened by a complicated family legacy—and a dissolute rock star with more money than self-worth and an addiction problem. Despite the fact that these two damaged individuals would not be a good fit for each other, they found themselves drawn together.

I liked the bones. What I didn’t like was what happened when I tried to build the story around a female detective.

She wasn’t less. I made her brilliant, capable, and driven. But the moment she stepped into a room with male colleagues, with suspects, and with the institutional machinery of law enforcement, something subtle and persistent happened: the narrative kept sliding out from under her. Her brilliance read as quirky rather than authoritative. The men around her held the institutional weight. She was constantly navigating not just the case but also the gendered friction of existing in that space as a woman. And the romance itself? The power dynamic between a female detective and a male rock star with wealth and cultural capital tilted in ways I kept trying to correct and couldn’t. The story collapsed under its own structural problems.

This wasn’t a failure of imagination. It was a structural reality.

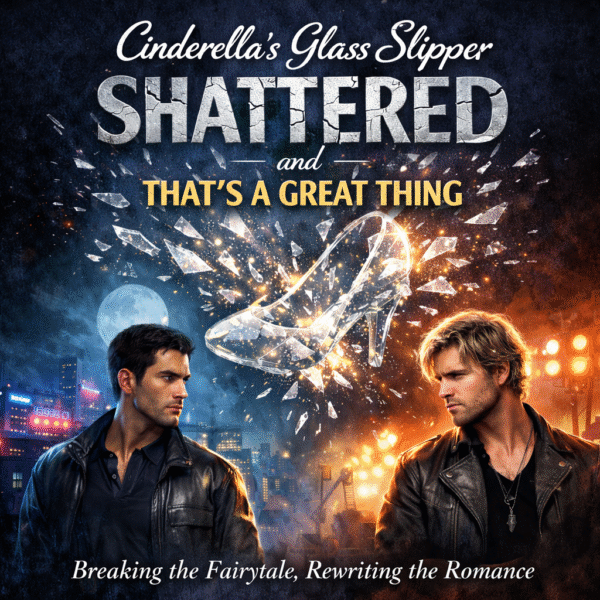

The Cinderella Problem

The romance genre has long had a Cinderella problem—and I mean that in the most specific, structural sense. The dominant romantic template for women in fiction is, at its core, about rescuing a woman from circumstances controlled by men. She needs saving—from poverty, from social precarity, from the predations of villains—and the hero provides that salvation, often by lifting her into his world rather than meeting her in hers. Even well-intentioned versions of this trope—the ones where the heroine has fire, wit, and independence—still tend to place institutional and social authority in the hero’s hands. He holds the castle. She gets to live in it.

Women readers are extraordinarily tired of this. Not universally, not categorically—there are readers who love the fantasy and that’s completely legitimate—but there’s a significant and growing audience of readers who want something the traditional male/female romance template makes structurally difficult to deliver: a story where the romance is between genuine equals, where desire doesn’t carry an embedded power imbalance, and where neither character is ultimately dependent on the other for their standing in the world.

This is a big part of what MM romance has quietly become for a large female readership. It is not primarily about gay sex. It is about romance and desire framed within a relationship between equals—two people navigating vulnerability, connection, and love without the architecture of gendered power distorting every scene.

What Reframing Did for The Justix Files

When I made Jessick and Rik both men, the story came alive.

Detective Jessick, bearing the weight of a renowned law enforcement family, dedicates a significant portion of the series to fighting against his own submissive tendencies—which feel, to him, like a betrayal of what he’s supposed to be. Rik has everything Jessick doesn’t: money, fame, and the world’s attention. What he lacks is a coherent sense of self and an addiction to substances, as he struggles to remain sober. They are broken in completely different ways. Neither of them can save the other. They can only, potentially, be honest with each other.

The power dynamics in that relationship are rich and intriguing and constantly in motion—which is exactly what I wanted. But they’re character dynamics, not gender dynamics. I’m not fighting the structural gravity of heterosexual romantic convention every time they’re in a scene together. I’m just writing about two human beings in all their complication.

That’s what removing the gendered framework gave me—the freedom to write the actual story.

Why This Matters Beyond The Justix Files

I think about this a lot in the context of my work as a ghostwriter, because my clients are almost exclusively writing female protagonists in heterosexual romances. Agency is non-negotiable in that work—readers will abandon a story if the heroine doesn’t have genuine authority over her narrative. It’s one of the most consistent craft challenges in the genre, and it’s not because writers don’t understand what agency is. It’s because the dominant romantic template actively works against it.

MM romance sidesteps that structural problem entirely. It doesn’t mean the relationships are less complex or less emotionally resonant—Jessick and Rik would tell you quite the opposite—but it means those complexities emerge from character rather than from a centuries-old inheritance of who gets to hold the power.

Cinderella isn’t dead, exactly. She still moves enormous amounts of product. But her glass slipper has shattered. For the stories I want to tell—the ones with two fully realized protagonists meeting as equals in all their damage and difficulty—she’s not the right template

The Justix Files is the result.